Kenny King says town shares his honor

By Roger Estlack,

Clarendon Enterprise

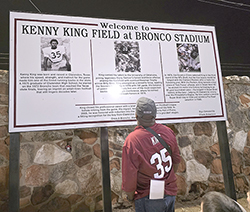

Maroon letters now spell out “Kenny King Field” on the grass of Bronco Stadium, but the man who put Clarendon on the map with two Super Bowl championships says the honor is not solely his – it belongs to the community.

Enterprise Photo

The formal naming ceremony came during halftime of Clarendon High School’s game with Quanah last Friday. It was a day filled with memories, a pep rally speech by King, hundreds of autographs, and a Bronco victory that propelled his alma mater to the playoffs. On Saturday, King reflected on what the naming of the field means to him.

“A lot of people said they’re happy for me and proud of me,” King said, “but it’s not just me. It’s us. That’s why I wanted my friends and family and classmates with me last night. Without them, there is no Kenny King… or Kenneth King.”

He said the full impact of the event probably won’t hit him until he’s home on his patio with a cigar and some Buffalo Trace.

“For everybody that came last night, it meant so much,” King said. “So many people made it possible, so many friends, and my wife, Wanda.”

The admiration and respect today’s Broncos had for Clarendon’s former #35 was evident before the game and off the field, and King loved watching the boys play on his old stomping grounds.

“Those kids played their hearts out,” King said. “I had some conversations with a couple of them, the kind Gene Upshaw had with me as a rookie. It was words said in gentle manner that such that you want to listen.”

King said the Broncos will themselves to win and that he was proud of them and their coaches.

“I saw bees swarming. They group tackled. They were on fire. Thank you to the Clarendon Broncos for making my night special.”

In high school, King was known for his speed and strength as a running back. He was part of the 1972 Broncho team that reached the state finals before he graduated in 1975. Barry Switzer recruited him to the University of Oklahoma. His father wanted him to take an offer from Texas A&M, but King said believed from OU he could go to the next level. In 1979, he was drafted by the Houston Oilers and then joined the Oakland Raiders the following year. He set a record in Super Bowl XV, catching an 80-yard touchdown pass, to help beat Philadelphia, and then got another Super Bowl victory in 1984.

It’s an impressive resume for a kid from a little town in the Texas Panhandle, but King says he owes it all to the sacrifices of his late parents – Walter and Louisa King – and some really good coaches and teachers in Clarendon.

“My mother, everybody loved Louisa King,” he said. “She never went to a game. She would sit outside that east gate and see what she could but wouldn’t go inside because of her religion. She came to New Orleans for the Super Bowl but stayed at the hotel. Her pastor would tell her it was okay, but she had her convictions.”

Mentorships in school started in P.E. classes and continued through the years.

“Coach Pete Bromley treated everybody fairly – boys and girls,” King recalled of junior high. “I was 4’11” and 116 pounds in the eighth grade as a starting halfback. I was aloof in a game against Claude, and he moved me back to third string and put two seventh graders ahead of me. He eventually put me back in the game, and I never looked back.”

Coaches like Jack Hall, Clyde Noonkester, and Jeff Walker made an impact as well.

“I was ‘coached,’ and that makes a difference in a player’s life,” he said.

Clarendon, King said, is a place of great leaders and great teachers.

“Mrs. (Claudine) Todd was by far my favorite. She was so good to me, and Mrs. Stave (Jean Stavenhagen) was the other favorite,” King said. “I was very arrogant as a senior, but they would reel me in and not let me get away with it.”

Going to OU was a different kind of football and led to new challenges but also more opportunities. And after his football career, he still had people who influenced him, specifically Dino Colantori, who was his first manager at UPS. Through it all, he kept Clarendon and friends, family, and mentors in mind.

“The trials, the tribulations, people don’t know,” King said. “I didn’t want my hometown to fail. Anything I did reflected on Clarendon and impacted my family and friends. I would party, but I would never allow myself to get involved in bad situations.”

King said he had the right foundation and support, and he tried to maintain a level of success in professional sports and later in the corporate world because he felt it reflected back on his hometown.

Now, three years into his retirement, King is truly grateful for his life and for what Clarendon has done for him.

“It’s my name on the field, but we did it together,” he said. “Clarendon, Texas, I love you. Thank you for being my friend. I will be back.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.